兩聲道

CD機 | MD機 | SACD機 | DAC | CAS | 合拼擴音機 | 前級擴音機 | 後級擴音機 | 接線 | 喇叭線 | 揚聲器 | 耳機 | 耳機擴音機 | LP產品 | 膽機產品 | 開卷式錄音機 | 音響配件 | DIY音響 | 電源 | 家庭影院

電視機 | 投影機 | 錄影機 | DVD影碟機 | Blu-ray影碟機 | 多媒體播放器 | 機頂盒 | 多聲道擴音機 | 多聲道揚聲器 | 多聲道影音組合 | Mini音響組合 | 重低音揚聲器 | 輔助設備 | 同好會

同好會 | Accuphase | B&W | Burmester | Denon | Jadis | KEF | KRELL | Luxman | Marantz | Nuforce | OPPO | Pioneer | TEAC | WEISS | News

News | Blog | 其他

其他 | 所有 |

| 影音天地主旨 ﹝請按主旨作出回應﹞ 下頁 尾頁 | 寄件者 | 傳送日期

|

| [#1875] Tone Control #2 再沒有人敢設計出一部前級擴大機有專治小喇叭陽痿" x2 |

spyder 14.xxx.xxx.191 |

2017-11-28 19:58 | |

|

|

|||

[#1874] Tone Control #2   LYNGDORF TDAI-2170 – 房間音響修正擴音機,觸動,來自技術與北歐品味! http://personalaudio.hk/2017/11/27/lyngdorf-tdai-2170/ 最後修改時間: 2017-11-27 22:14:58 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-27 22:14 |

[#1873] Tone Control #2  (文章節錄自台灣音響論壇2010年1月號第256期 P.276-277頁,由專欄作家不默先生撰寫,談及 QUAD 44前級上的 TILT CONTROL / BASS LIFT如何了得) 古早人談音響 挑鐙集 : 追求平直的不二法門 - 敲敲打打 (下) 說真的,不默向好友拿來QUAD 44時,身邊的器材都己是挺好,喇叭也夠大,頻譜也挺平直的了,所以對QUAD 44設計者的苦心,只覺麻煩,真是「茶煲」呀! -----不默想,海上有逐臭之夫,QUAD 44的設計者也真的不怕麻煩,自找麻煩,其中必有道理! 幸虧不默肯想、愛玩,也常常「冒險」地去試不同事物。等到不默把44接上當年的英國精品小喇叭,才赫然發現此翁之意原來如此! 原來如此!   原來QUAD 44根本是替英國的精品小喇叭量身設計的。他老人家一定不憚煩的把所有小喇叭的特性、頻譜曲線測試下來,發現它們即使在喇叭設計者委屈求全,如何犧牲效率、犧牲高頻、分音線路如何敲敲打打,仍然有病一同的有它回天乏術的扭曲了的曲線。就是1kHz以下的走勢,和到了300Hz開始,就各走各路的低頻陷縮,甚至到了80Hz、60Hz、50Hz,甚至以下的頻率如何「不忍卒聽」。於是設計者就替這些小喇叭打造了「反勢」的3dB、6dB、9dB曲線 (天可憐見,他也一定也無法打出一個簡單好用的可調微的線路,所以只能有三個定點的選擇) 。 當然,後級擴大機如果在20Hz ~ 30Hz附近增益10dB ~ 15dB,這真是不得了的負擔! 但如果您只聽1W左右的音壓,而擴大機卻有100W,那麼,100W之於1W,就是20dB的增益,上述的曲線扭轉、仍然是可容忍而未過荷的範圍。所以 QUAD的後級就設計成100W。信不信由你,如果你把 QUAD 44左控制捍推到「9dB」,管風琴低頻出現時,如果100W的擴大機有過荷警言,它很可能就告訢你: 「過荷了! 」  「頻率平直」是害人精! 事實上,不默把 QUAD 44 放在西雅圖小木屋,搭配了三菱太祖級精品小型擴大樓,聽低音多的段落時,QUAD 44 那個+9dB的調整,就把三菱的LED 推到75W以上的過荷輸出! ------ 只是,別怕,那個打不死的 IMAGE英國小喇叭,居然發出一板一眼,十分正確的聲音。 啊! 啊! 啊! 英國小喇叭如果用上 QUAD 44那條回天有術的+9dB曲線的敲敲打打,竟然得到還算挺「對」的表現! 英國精品小喇叭的使用者多如牛毛,當年用過QUAD 44來配它的用家也所在多有! 只是,不默相信,當年用家不知道它們當年為甚麼是「鐵配」,更不知英國小喇叭配上 QUAD 44能發出這麼「正確」的聲音。------ 也許把 Rogers LS3/5A操到100W輸入,沒有用 QUAD 44的反扭曲控制,也挺好聽的,不默當年是如此聽,不默身邊的Hi-Fi高手群也是如此聽,卻空辜負了 QUAD 44設計者的一片苦心! 想來想去,就只有一個害人精,所謂「頻譜平直」的迷思,而不敢去配 QUAD 44,有了QUAD 44也不敢扭扭那個 3、6、9dB的控制抦! 走筆至此,不默不禁仰天長嘆一聲! 「頻率平直」害人啊! 到如今,QUAD 44早己絕種,也再沒有人敢設計出一部前級擴大機有專治小喇叭陽痿的通病,也許吧! 病人千百種,等化器也早已遍地開花、沒有一種簡便的成藥能把各級陽痿簡便通吃。而用家呢,對自己使用的喇叭,在各不同輸入功率之下的曲線圖也一無所知。其實廠家要量好附上也不難,只是它們更怕這附上的頻譜,準把客人全嚇跑了! 於是聯手壟斷,大家都不提,一齊打迷糊仗,用家就各憑本事,自己去調味啦! ------- 你知道不默在等化器前浪費了多少青春歲月嗎?! 可憐呀! 頭髮白了,也沒搞清楚,頂多是自以為是的列了一張從20Hz到20kHz之間的加減減紀錄,沒過了幾天,又在沒自信心之下一再修正、再修正。 用來用去,還是 QUAD 44的3、6、9dB來得簡單方便啊! 不默在此向當年的QUAD 44設計者肅立致敬。 最後修改時間: 2017-11-27 07:02:42 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-27 06:54 |

| [#1872] Tone Control #2 當年今日:Cello 128 萬套裝組合 http://hifireview.com.hk/19920901/cello-1280000-set/      最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 16:12:44 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 16:12 |

[#1871] Tone Control #2  Hi Fi 基礎談 十六:音色 玩 Hi Fi 的人,似乎個個都知二十至二萬是怎麼的一回事。但講深一層卻又覺得香港人對音響的物理常識實在不求甚解得很。小學及中學的課本,對音響學常識的提供是膚淺得可憐。唸電工電子專科的青少年更不注重音響學。二十至二萬,對一般人來說,是人耳聽覺的敏感範圍,那是聲波每秒鐘振盪的次數。人耳可以聽到頻率由 20 赫至 2 萬赫之間的音響,數目低的頻率是低音,數目高的就是高音。大提琴出低音,「丁丁查查」出高音。所以,大提琴的聲音是從低音喇叭播出,丁丁查查的聲音是從高音喇叭播出……於是,就不斷有人問:「長笛的聲音,是屬於那隻喇叭的範圍?」或者:「中音喇叭壞了,會影響那幾件樂器的聲音?」 好多人都以為,各種樂器之間音色的分別是因為它們發出的聲音頻率高低不同。他們對音響的構成根本毫無認識。事實上,如果自然界一切音樂的形成都像這些人所想的那末簡單的話,這世界就不可能有音樂的存在……小提琴發出的 A=440 赫,和長笛奏出的 A=440 赫音響將完全沒有分別。它們跟訊號產生器發出的 440 赫正弦波聽起來也一模一樣。換句話說,世界上一切音響的成份都只是純正的弦波。人類語言的音色再無男女老嫩你我之分。甚至,你的叫聲和狗吠聲也一模一樣! 一件發音體在空氣中振盪,它本身及環繞着它的空氣都會產生一連串頗為複雜的反應。音響的構成,殊非多少「赫」那末簡單。我們日常聽到的一切音響,都是由一羣頻率不同及響度各異的音波合成。這個自然現象,正好比把一塊石子投入水中,水面形成的波紋是環接着一環向外擴散,同時中間又夾雜無數細微的水紋。 基音與諧波 我們把一個音響的最低頻率稱為「基音」,則基音之上,一定附有很多諧波(Harmonics),諧波的波長,依次是基音的一半,三份一、四份一……等。換言之,諧波的頻率,都是基音的倍數。每一個音響的基音,諧波和泛波等音構合的成份不同,就是自然界億萬種不同音色的來源。一般人或以為構成音響的最重要部份是它的基音,這是不正確的,很多種樂器的音色,基音只佔全個音波的極少百份率。在重播這些音響時就算將基音完全濾去,聽者都不會發覺,這真是不能想像的奇妙現象。因為,一個 50 赫的音波如果被移去了基音,它根本就是一個以第二諧波(2nd Harmonic)為基音的 100 赫音波,連音調都升高了,耳朵仍然可能不覺察。可見,人耳的敏感度有時也很遲鈍。 總言之,Hi Fi 之所以能夠成功,全然是因為聽覺的愚蠢及妥協性。人耳聽音樂,只要有幾成似就過得關。電話聽筒傳輸的週率不外乎整個聽頻帶的十幾二十份之一的範圍,人耳卻有本事從這狹窄的區域裏分得出人聲的音色甚至大部份樂器的音色。即是說,一台普通的三路揚聲器,如果把它的高音及低音單元關掉的話,中音單元的有限度重播也已經有條件表達出大部份的樂器的音色。因為,一切樂器的基本發音,佔了極大部份都是由二百赫至三千赫之間的音波。連丁丁查查的發音都以中音為基本。事實上,丁丁(即三角鐵)在敲下去的瞬間所猝發的音波,低至 1.2K~1.5K 赫。它的「聲尾」卻高至 10.4K 赫。而查查(即銅鈸)在對碰時所猝發「襟」一聲的「聲頭」,亦約只是 2K 赫,它的「聲尾」就扳升至 20K 赫。 講到「聲頭」和「聲尾」,終於入題了。原來每一種樂器或自然音響(除正弦波。其實,在日常生活環境裏,我們好少機會聽到純音波。就算用頻率產生器經揚聲器出來的純正弦波,經過空氣進入耳膜之時已被環境的反射改變了它的純度),它的結構都有聲頭聲尾之分,聲頭才是決定音色的重要部份。把查查的聲頭除去,它的音色就不再是「查……」而是「沙……」。把丁丁的聲頭除去,它的音色就不是「丁……」而是「英……」很多樂器的發音,又例如小提琴和長笛,它們的音色分別,在於聲頭;聲尾的音波結構就頗為相似。一字咁淺,Hi Fi 重播之道,貴乎要準確地再造出一切聲頭的音色。聲頭音色的建立,永遠都要靠快過閃電的一剎那。Hi Fi術語,稱為瞬態響應。 神經綫音色之謎 發燒友一聽講瞬態,就完全明白曬,甚麼 TIM,甚麼 Slew Rate……口水多過茶,講成日都得矣。TIM 是瞬間互調失真,特性很難準確地紀錄下來。Slew Rate 是擴大器在一個單位時間內所能處理的電壓升降率,比較貼切的中譯是「變壓率」。 瞬態特性優異的擴音器,只是發燒器材必備的一環。其他一切配搭,只要有一件東西慢了一慢,最終的重播質素亦必蒙受不可救藥之破壞。Hi Fi 重播和接力賽跑的分別在此。接力賽裏,如果其中一名運動員跑得稍為慢半秒,他無疑影響整段賽績,但卻不致影響其他隊友的速度。Hi Fi 環裏,唱頭的瞬態是一定影響後級的瞬態,因為後級的性能再好,也無法把交到手上本來就已經是慢了的訊號「加速」。 神經綫音色之各有不同,也是在傳送聽頻訊號的速度在不同週率有分快慢之不同。筆者完全相信這是影響導綫音響個性的主因。一切電阻、電抗、電容,接觸點等等,都干擾某部份頻率運行的速度。這解釋正好把最複雜的千頭萬緒歸納在一個結果上。導綫沒有將訊號放大的本事,只能將訊號衰減或使訊號與放大器之間互相調製產生鈴震、諧震。這些問題,和揚聲器連在一起,便演變成亂世佳人。但,守則仍然在:已經損失了的或被拖慢了的訊號,不能再準確地尋回或重新加速。 喇叭是 Hi Fi 接力賽程上的最後一棒,由 CD、MC、LV 或 LP 來的音訊,都在這裏盡情宣洩,也是玩弄音色之人的最佳栽剪工具。由二千至五十萬元,都有其本身音色。老爺古董獨有的某類失真,可能是一些發燒友死攬住一對喇叭二十年不放的原因。 尊耳生在閣下的骷髏上:死無對証。 http://hifireview.com.hk/20171124/hi-fi-%E5%9F%BA%E7%A4%8E%E8%AB%87-%E5%8D%81%E5%85%AD%EF%BC%9A%E9%9F%B3%E8%89%B2/ 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 15:50:58 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 15:50 |

[#1870] Tone Control #2  The Inimitable Manley Massive Passive Equalizer | Universal Audio https://www.uaudio.com/blog/hardware-manley-massive-passive-overview/ Manley Massive Passive Sound Demo Mastering with Manley Massive Passive 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 15:18:22 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 15:17 |

[#1869] Tone Control #2  http://www.burwenaudio.com/images/CELLO_AUDIO_PALETTE.pdf  Cello Palette Preamp Equalizer Cello Palette Preamplifier | Stereophile.com https://www.stereophile.com/solidpreamps/692cello/index.html 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 15:21:01 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 15:11 |

[#1868] Tone Control #2  FULL ARTICLE: Back to Musical Realism: The Quad System - Part 1 Equipment report by Tony Cordesman | Aug 04th, 2010 http://www.theabsolutesound.com/articles/back-to-musical-realism-the-quad-system-part-1/ +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ EXCERPT:  "If you wonder why I should focus on making ordinary recordings seem more musically accurate, let me remind you that TAS was founded around the search for musical realism and not perfection in engineering – a goal that at least part of the recording industry and part of the high end seems to have forgotten. It is also a fact of life that I have well over 1,000 CDs whose problems become all too apparent on a reference system that is tuned to be as accurate and revealing as possible, and which lacks tone controls and any other way to compensate for the problems in the recording. I spend a good part of my life traveling to areas where listening to live music is virtually the only sane way I have to relax. Even in the bright halls and in Asian countries where music often has a higher pitch, I never hear the level of upper midrange energy, the lack of lower midrange warmth, and the hardness that I hear in far too many US and European classical recordings. I’ve heard musicians play badly tuned instruments, and bad musicians become shrill through mistakes or poor judgment, but I have never heard good musicians play in ways that alter timbre and produce artificial detail at the cost of hardness to the extent that many CDs and some SACDs do.  Go to any live concert of chamber music, listen to any other music emphasizing strings and woodwinds, listen carefully to massed strings, pay close attention to soprano voice, or simply listen to someone actually play a grand piano. Compare what you hear to far too many recordings played through some of today’s best and most accurate equipment. If you can’t hear the same types of musical detail when you stand only 10 feet away from a live musician, and if you can’t the same balance of “highs” when you listen to live music, you should not hear them on recordings. Here, I may disagree with many of my colleagues who listen primarily to popular music. With classical music, the issue is not whether you can hear something new – or more “detail” – it is whether you can hear what is musically natural and musically relevant.  2 A Strad should sound exactly like a Strad. 3 A Soprano’s voice should not emphasize breathing sounds and harden. A Steinway or Bosendorfer should sound like a grand piano, and never have hints of sounding like slightly off tune upright. A loud flute should be a source of pleasure, not irritation, and so the upper register of the clarinet. 4. I suspect we all have our own examples, some glaring and some more subtle. To provide more subtle examples that seem appropriate to high-end audiophiles, let me compare two recordings. The Pierre Fournier performance of the Dvorak and Elgar cello concerti on Deutsche Grammophon is a lean and hard remastering of a very good performance in spite of the fact these are full concertos. It becomes somewhat fatiguing and unpleasant to listen to without some help from a tone control or equalizer. In contrast, the Cleveland Quartet recording of Dvorak string quartets on Telarc is much more musically natural even though unsupported strings should normally have more treble energy. 3 If you want a practical example of what I mean when I say that a Strad should sound like a Strad, compare two very good and naturally balanced recordings that both use older instruments. Take the L’Archibudelli and Smithsonian Chamber Players recording of Mendelssohn-Gade Octet for strings [Sony Vivarte]. This recording uses all Stradivarius instruments. Compare it with the Smithsonian String Quartet recording of the Beethoven: The Early String Quartets, Op. 18, [Smithsonian Collection of Recordings]. The second recording uses instruments made by a variety of makers during the mid-1600s to mid-1700s. Even a slightly lean system will blur the sonic differences between them. 4 These problems don’t just occur with older recordings. Compare the natural sound on Larry Archibald’s recording of Antony Michaelson and the Michaelangelo Chamber Orchestra performing the Mozart Clarinet Concerto (K2622) [Musical Fidelity SACD] with the somewhat brighter and harder recording of the same work by Martin Frost and the Amsterdam Sinfonietta [BIS SACD]. These problems are far less apparent in popular, jazz and rock recordings, or in classical symphonic music and large ensembles. Problems in upper midrange timbre and the natural musical sweetness in the detail of instruments with large amounts of upper midrange energy are less apparent given the mix and instrumentation involved. They are all too common; however, in older CDs of chamber music, solo instrument, and small ensembles CDs, and they are also present in about 20-25% of today’s CDs and SACDs. They also are far more striking in recordings of older chamber music – and female voice and solo instruments like the violin, piano, clarinet, flute, etc. – than with orchestral music. The problems do occur with acoustic jazz percussion, piano, and sometimes clarinet and so on, but they are considerably rarer. At the same time, enough high-end audiophiles with very different tastes in music from mine do prefer “warm” tube equipment, and speakers with a rise in the bass and a dip in the upper midrange, to indicate that I am scarcely alone in worrying about these problems. There do seem to be a significant number of audiophiles who not only want system that are not colored but also want ones that emphasize the natural timbres and levels of detail in live music."  最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 14:56:21 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 14:50 |

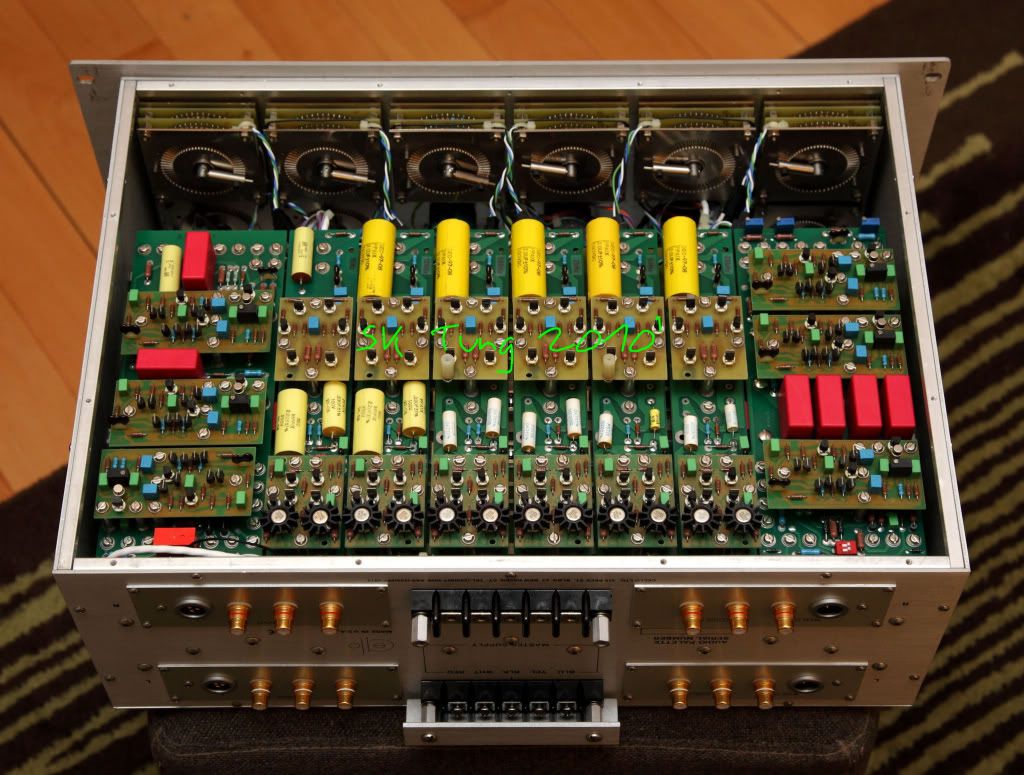

| [#1867] Tone Control #2 器材評論/劉漢盛 專門尋回正確聲音的等化前級 Cello Audio Palette MIV  圖240:Cello Audio Palette MIV維持了一貫的儀器外觀,但是轉起來的質感實在叫人感動得想痛哭流涕。  圖243:Cello Audio Palette MIV的內部頗為壯觀,這也是它要賣那麼貴的原因之一。 在正式進入Audio Palette MIV的世界之前,請先看看以下幾則故事: 有一個線王,他在線材上的花費以經超過一百萬。每次,只要聽到某張CD聲音不對,他就興起換線的念頭。但是,每次換線也錦能得到短暫的滿足而已。在一個機會中,他試用了Audio Palette MIV調整出來。從此三千寵愛於一身,線王不再換線. 有一位老玩家,他說他連32段的等化器都玩過,仍然無法肯定等化器的正面效果,更別提只有六段調整的Audio Palette MIV。因此,一直對Cello Audio Palette MIV持有負面的 評價。有一次,他抱著姑且一試的念頭試用了Cello Audio Palette MIV。過了一個月後,他掏錢將Cello Audio Palette MIV買下。 還有一位金耳朵,它用Cello Audio Palette MIV來訓練耳朵的聽力。日復一日,他的耳力逐漸精進。據說,現在他已經可以分辨出正負0.5dB的調整差異。 有一位換機狂,只要他發現有好的、貴的器材,他就忍不住想換。由於買得太多,家中器材堆積如山,為此夫妻間常起爭執。有一次,夫妻偕同試聽Cello Audio Palette MIV,由於太座學過樂器,一聽之下認為Cello Audio Palette MIV能夠調出正確的樂器音色。這次他不反對了,反而慫恿老公買下Cello Audio Palette MIV。 最後一則故事:一位音響迷有個學鋼琴的女兒,這個女兒老是在父親頭上潑冷水,說他的音響系統所發出的鋼琴聲音不對,惹得老爸大罵女兒不懂音響。後來老爸買了Cello Audio Palette MIV,從此以後她說老爸的音響像真的一樣。 以上幾則故事您信也好、不信也好,當神話聽也好,那都不是頂重要的是,因為這些故事都是別人告訴我的,我也僅是姑且聽之。不過,以下的經驗就是我自己「玩」Cello Audio Palette MIV的親身體驗,我十分樂意毫不失真的傳達給讀者另一扇欣賞音樂、調整音響之門。 話匣子一開,我們先聊些別的。只要一提起Cello,大部分的人都要先皺起眉頭,說:「那些東西太貴了。」沒錯,包括我在內,都認為Cello的東西不便宜,連我都不敢輕易嘗試。可惜,因為Cello的產品並不是一般人能夠有機會接觸到的﹝有許多人摸過Cello的旋鈕?﹞;Cello有一本闡揚自身設計製造哲學的「白皮書」買來看過的人也不多。因此,大多數的人多少都會不服氣的在心裡嘀咕:「憑Cello那冷冰冰像儀器般的外表就要賣那麼貴的價錢,我又不是凱子,怎麼可能去買它?」。老實說,對於Cello產品那冷冰冰的外表我也不欣賞。可是,我在這裡必須正色的告訴讀者們:「Cello所發出來的音樂並不是冷冰冰毫無表情的,它反而是活生生的熱血沸騰的。更有甚者,它那內部毫不妥協的追求完美精神,已經可以說是浪漫情懷的極致發展。」  不要以為我是空口說白話。在此,我舉一個例子做見證: 大家在Cello Audio Palette MIV面板上都可以看到五十九級音量控制旋鈕。這個旋鈕是康乃狄克州一家很有名的精密金屬加工公司F.J.Weidner&Sons所產製﹝包括其他旋鈕與面板亦然﹞。從一九七二年開始,Mark Levinson就與他們合作。在Mark Levinson完美品質與美感的要求下,這些精緻精密的旋鈕一個個的用手工做出來。您可以看到整個旋鈕都是用不鏽鋼車成,那些刻度與數字都是手工刻上去的,其精度為0.001英吋。在旋鈕裡邊由四塊板子組成。最上面那一塊是純銅塊經過研磨後鍍上鎳,然後在上面刻了六十道溝,作為旋轉時每個刻度的定位用。最下面那塊板子也是純銅塊研磨而成,作為上下固定整個旋鈕之用。中間二塊則是線路板,這二快線路板每塊都是銅鍍再鍍金,然後以手工銲上59顆1%精密金屬皮膜電阻而成。凡是自己銲過級進式音量控制器的人都知道每一級的接點很重要,如果接點磨損或氧化,對於音質的損害將無可菇計。為此,Mark Levinson用白金/鈀合金做成接點,以保證接點的可靠性。最後。旋鈕轉動的軸心滾珠軸承也是不鏽鋼製成。這樣一個幾成完美的級控制器,其二聲道的誤差有多少?才0.1dB而已。要知到,這是個很驚人的數字,一般二聲道音量控制器的誤差要找到0.5dB的已經很難,有的甚至會高達1.5dB或3dB。我敢說 Audio Palette MIV成本最高部份就在於那些旋鈕與機箱上面。不要做得那麼精密,然後將Audio Palette MIV賣便宜一些不好嗎?當然好!以價位而言,Audio Palette與Palette Pramplifier。當然以價位而言,Audio Palette與Palette Pramplifier仍不是真正一般大眾所能負擔得起的。 其實,我上面說為了一般人負擔得起才有Audio Palette與Palette Pramplifier是不恰當的說法,Audio Palette是 Mark Levinson離開 Mark Levinson公司之後的第一創業作﹝一九八五推出﹞,它只是作為一部等化器之用。後來,結合 Audio Palette與 Audio Suite前級的優點才有了 Audio Palette MIV的出現。  Cello Audio Suite & Audio Palette | cello music and film system by Mark Levinson Palette Pramplifier則是生產來給「一般人」用的。在此,我說「一般人」並不是在貶低音響消費者, Audio Palette 與Audio Palette MIV真的有很多是賣給知名的錄音室當作等化器使用。例如Michael Cuscunaz Mosaic Records錄音室﹞、 Bob Ludwig zMasterdisk錄音室﹞,' Tom Jung ﹝DMP錄音室﹞、 Dennis Drake ﹝Polygram錄音室{ Ted Jensen zSterling錄音室{ Net Johnson zRCA錄音室﹞、Steven lnnocenzi ﹝Atlantic錄音室﹞、 Christa Maria Bilz zSonomaster錄音室﹞等。從名稱上,我們可以知道 Audio Palette MIV與 Palette Preamplifier是具有前級功能的等化器,而 Audio Palette僅是等化器。 Audio Palteet MIV在面板上並沒有刻上MIVzMultiple Input Version{字樣,它也僅是寫著Audio Palette而已,不過,如果仔細看上排第二個旋鈕,就會發線Audio Palette MIV表示的是四組輸入,而Audio Palette是Monitor/Center。 為什麼Mark Levinson會選一個等化器作為東山再起的創業作呢?等化器不是一個惡名昭彰的東西嗎?音響迷都知道多支香爐多支鬼的道理,任何的環路中不是越少串入別的東西越好嗎?當然,這個道理是顛仆不破的,不過,讓我們從另一個方面來思考這個問題。首先我們要知道,在錄音室中錄製音樂時,為了平衡麥克風的先天缺陷、空間的缺陷以及監聽空間,喇叭的缺陷,所有的錄音都會使用等化器﹝基本上錄音室的控制台就是一個複雜的大等化器﹞。這也是 Audio Palette MIV會賣給錄音室的道理。請注意,經過了這些等化過程之後,製成的母帶可以確定完全適合該錄音室、錄音師與製作人的要求。然而,它會剛好適合您自身的喇叭、擴大機、空間條件嗎?答案幾乎是否定的。為此, Mark Levinson提出了一個一般人都誤解多年的正確觀念:等化器並不是用於等化室空間的頻率響應曲線,而是試圖將正確的音樂透過等化器找回來。  然而,從古至今,我們很少聽說有人對於傳統美三分之一八度一段的等化器有極高的評價的,這也是大部份唇音響迷對於等化器持反對意見的原因。為什麼多段師等化器對聲音有負面影響呢?道理很簡單,相位失真是其一、調整困難是其二、損害原有音質是其三。既然等化器有這些問題,難道 Mark Levinson的等化器就沒有嗎?請注意,Audio Palette MIV的等化級段只有分為15Hz、120Kz、500Hz、2KHz、5KHz、25KHz六段而已,這已經解決許多多段多相位失真以及調整困難的問題。再者,如前所述,Audio Palette MIV以近乎完美的精密要求製造,因此對於音質的影響也降到最低。 為什麼會選這六段來等化呢?說到這裡就必須請Richard Burwen這個人上台接受鼓掌。Richard Burwen 是一個資深的錄音師,也是長久以來Mark Levinson 的好友與顧問。他積四十五年錄音室的經驗,研究出只造在這六段關鍵點切入調整,很快就能掌握到整個頻段的聲音平衡zTonal Balance{與透名明感。這個原始架構交到Mark Levinson 手上,再交到Cello的工程部傅副總裁Tom Cloangelo手上,於是線路架構出來了,金屬加工也出來了,這就是Audio Palette MIV 的誕生。 「等化器就是等化器,說的再神也不會改變其等化器的本質。」許多資深音響迷一定會這麼說。不錯,在我還未接觸到Palette Pramplifier 與Audio Palette MIV之前,我也是這麼想。上次外燴接觸到Palette Pramplifier之後,我的觀念開始轉變。這次,透過在家裡「玩」 Audio Palette MIV,我有更進一步的認識。在此,我要說:您不妨拋開成見,看看 Audio Palette MIV會帶給您什麼樣的經驗。為什麼我會一再使用「玩」Audio Palette MIV的字眼呢? 這是因為我真的是在玩 Audio Palette MIV,而不是像往常一般,在嚴肅的聽音樂。而且,我還玩的很高興,甚至小有心得。在此,我將此心得與讀者們分享。 Audio Palette MIV的面板很整齊,就是被上下二排旋鈕所佔滿而已。上面那排司功能,下面那排司等化。讓我很簡單的就說明這些旋鈕的功能。從上排左邊起講,最左邊二個是左右聲道獨立的輸入調整。這是最講究二聲道平衡調整。第三個是絕對相位開關,它分為左聲道反相、右聲道反相、零度正相以及二聲道合併反相等四段。再來是等化的In、Out與Blend。這個Blend的功能就是增強40Hz以下頻率3-.6dB。再來是輸入端子﹝輸入阻抗為10K歐姆﹞與三組RCA輸入端子﹝輸入組抗為1Meg歐姆﹞。讀者們是否注意到,Cello前期的輸入組抗要比一般前級高很多。為什麼?這是他們經由實際聆聽得來的經驗,他們發現數位訊源經由高阻抗輸入時,聽起來LP更像訊源,所以將RCA端子的輸入阻抗提高至1Meg歐姆。在此順便一提,Audio Palette MIV的平衡式端子並不是一般通用的XLR端子,而是Fischer端子。道理很簡單,Mark Levinson認為Fischer要比XLR好得多。上排最右邊那個旋鈕就是音量旋鈕。  接下來說到下排的等話部份。最左邊那個是15Hz正負25dB,第二個是120Hz正負14dB,第三個是500Hz正負6dB,第四個是2KHz正負6dB,第五個是5KHz正負12dB,第六個是25KHz正負20Db。選這六個頻率切入是Richard Burwen的45年經驗所致,而每段調整的範圍有的才6dB有的高達500Hz、2KHz中頻處,調整的幅度只有6dB。它代表著只要調整一點點=人耳就會敏銳的感受到。而15Hz、25KHz二端呢?由於人耳對此二端頻率比較遲鈍,所以調整的幅度要很大。 Audio Palette MIV的精華都在面板上,背板實在沒什麼好提的。除了四組訊號輸入端之外,就是二組以Y型插鎖住的電源接端。讀者們一定會感到奇怪,怎麼前面極盡精緻精密之能事,而背面的電源線竟然那麼原始!一言以蔽之,Mark Levinson認為此處不需奢華,只要可靠就好。 以前,我曾看過Mark Levinson本人調整Audio Palette MIV,只見他很快的將每段旋鈕右轉到底、又左轉到底,然後慢慢倒過回來找到一處停止。將六段旋鈕都粗調過之後,它再逐個頻段細條。不需多久,他究很熟鍊的將一些不太美的聲音調成美妙動聽的聲音。以前,我看他的調整真的就是看熱鬧而已。經過我這次親自使用,我才體會到他為什麼要這麼調?如果要,該調整多少?換句話說,他在以自己的聽感經驗找尋該張錄音頻段是否凹陷或突出,並藉此將它們調到聽起來像是自然美妙的音樂為止。 而依我自己的經驗呢?我發現5KHz是得分之鑰,無論要調整人聲或哪種樂器,一定要先調整這個旋鈕。它就好像電燈的調汪器一般,亮度與透明感度馬上就出來了。如果不先從5KHz處著手,您將要多費許多手腳。 調完5KHz,接著該從哪段著手呢?此時就必須依照不同的樂器或人聲來分類了。如果是人聲,要先調500Hz,這個頻段絕對不能調出鼻音。調完500Hz再調2KHz與120Hz,此時,活生生有形體的人聲就會適當的出現。最後,再加入25KHz與15Hz。25KHz主司堂音氣韻,而且會讓聲音更甜些。15Hz則使低頻更加的紮實。若是要調低頻樂器,例如大提琴、低音大提琴以及爵士套鼓等,在調完5KHz之後,第一個要調的就是120Hz。請注意,在調120Hz時不要一下子就將中低頻調得太濃,如一來質感與樂器音色都會失去正確性。您應該再適當的調過120Hz之後,再以調整500Hz與15Hz來補實低頻的飽滿。 接下來要如何調鋼琴呢?還是老樣子,先調5KHz,因為它關係到整體的亮度與透明度。然後是調整120Hz。此時,鋼琴聲音的爽脆程度與顆粒的飽滿之間必須仔細調整,不要一味的追求低音鍵的豐潤。如果低音鍵太豐潤,在高音部份將會相對的失去靈巧。調過120Hz之後,再調500Hz與2KHz。等一切都差不多了,再調整25KHz與15Hz。一般說來,25KHz與 15Hz就好像味精一般,加一點點就好,不要一大湯匙一大'湯匙的撒下去。 弦樂群呢?還是先調5KHz,然後是500Hz與2KHz交戶調整。等弦樂的甜度、亮度、厚度都出來之後,再加上120Hz,使弦樂群聽起來更鬆軟些。最後,才加上25KHz與15Hz這二匙味精。依我的經驗,弦越群最難調,因為很難在鬆軟與黏滯、擦弦質感之間取得絕佳的平衡。 管樂呢?無論是木管或鋼管,在調完5KHz之後,還是先得從500Hz處入手,然後是2KHz,再萊才是25KHz與 15Hz。 打擊樂器呢?如果是大鼓、定音鼓等低頻段打擊樂器,可以先從120Hz處入手,然後再加上15Hz。此時,5KHz顯得並不是那麼的重要。如果是頻率較高的打擊樂器,例如鈸或三角鐵,那麼5KHz與2KHz就具有決定性調整的地位。然後再以調整500Hz來加重接觸質感的厚度。接著以調整25KHz來增加堂音的氣韻。 總結我自己調整的經驗,如果本來已經覺得音效不錯的軟體並沒有大幅調整的必要,頂多是加點修飾而已。如果是一些聽起來比較「老聲」的軟體,那Audio Palette MIV的用處就大了。 最典型的例子就是有些Mercury或RCA的老錄音CD,無論是您覺得聲音太硬、太粗、不夠細、不夠甜、不夠鬆軟,在Audio Palette MIV 的調整下都可以求得好的效果。若是您嫌Telarc的低頻過量或是聲音太軟,用Audio Palette MIV 來醫也包君滿意。不過,若是您想藉加重低頻與低頻的調整來再生恐龍的威力,那我勸你還是省省吧,因為即使Audio Palette MIV 將低音加重了,您的喇叭也未必承受得起。 聽流行音樂的人買Audio Palette MIV 有沒有用?太有用了!一些老爵士音樂與老搖滾樂經過Audio Palette MIV 的調整之後,簡直就是脫胎換骨。人聲有力渾厚起來了;腳踩大鼓的撲撲聲無比軟Q;生鏽的銅鈸也變成銀銅合金鈸。不僅如此,一些原本聽起來窄窄的音場,在適當的調整之後,整個音場的寬度與深度加了數倍不止;整個音場裡的聲音也豐潤得有骨有肉﹝古典音樂也是如此﹞。 Audio Palette MIV 對於改善房間的中低音頻峰值有沒有效?老實說,玩了那麼久的Audio Palette MIV ,我從沒有拿它來對付房間中的低頻峰值。一來我的房間中低頻峰值並不明顯;二來我深深的為Audio Palette MIV 在讓音樂更自然更真實的調整能力上著迷,因此也沒想到要用Audio Palette MIV 去對付中低頻峰值。如果您真要用Audio Palette MIV來改善中低頻峰值,那也免驚。Audio Palette MIV在120HZ處有正負14Db的調整幅度,我相信對付一般中低頻峰值綽綽有餘。 訊號在未經Audio Palette MIV的等化線路,與訊號經過Audio Palette MIV六段調整歸零的情況下有什麼不同?我的意思是直接旁掉等化線路的訊號與歸零等化的訊號二者聽起來有什麼不同?如果相同,就表示Audio Palette MIV的等化線路音染極低。反之,就是等化線路有音染。要做這個測試,您可以利用面板上等化的In/Out檔來試,在切換的瞬間,您可以感覺有一點「不同」,但是我並沒有感覺「變壞」了。 在使用Audio Palette MIV之後,是否每撥放一張CD就要重新調整一次?理論上是如此,不過我自己都沒有那麼發燒。將Audio Palette MIV裝上的這些日子,除非是我要寫Audio Palette MIV的這篇報導之用,否則一般能夠入耳的音效我並不會刻意去調它。 http://audioart.audionet.com.tw/0Review2002/076/Equipment/02Cello.htm 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 15:06:26 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 14:42 |

| [#1866] Tone Control #2 等化器的調整方法 http://stingsti.blogspot.hk/2013/07/blog-post_24.html 幫聲音加上更多的個性與顏色,一次搞懂EQ的世界! @ Balanced Audio Lab 平衡音訊實驗室 :: 痞客邦 PIXNET :: http://a85115230.pixnet.net/blog/post/321880654-%E5%B9%AB%E8%81%B2%E9%9F%B3%E5%8A%A0%E4%B8%8A%E6%9B%B4%E5%A4%9A%E7%9A%84%E5%80%8B%E6%80%A7%E8%88%87%E9%A1%8F%E8%89%B2%EF%BC%8C%E4%B8%80%E6%AC%A1%E6%90%9E%E6%87%82eq%E7%9A%84  |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 14:41 |

| [#1865] Tone Control #2 Tone controls, the ear and the audiophile - curse or saviour? 30-06-2012, 10:38 AM Now this is a question that falls neatly into a speaker designer's arena, since loudspeaker design is all about 'shading' energy between one frequency band and another, and completely unlike the audiophile amplifier designer's brief where he will go to lengths to (hopefully) ensure that there is a completely flat response across the audio band. By 'flat' we mean that the energy (or voltage or loudness or frequency response: really all the same thing) will have no emphasis or leanness in one band of the frequency spectrum (the audio band) compared with any other. At least, that is what I would hope a serious audiophile amplifier designer would set as his working goal. A speaker designer has to consider the frequency response (= loudness v. particular frequency bands across the entire audio band) not as measured by a voltmeter in a laboratory under steady state conditions, as you would an amplifier, but after those volts are converted into sound by the speaker and then blasted into 3D space by that loudspeaker radiating (uncontrollably?) in all directions with the room absorbing quite differently in particular audio bands at different angles relative to the speaker. For example, if there is a deep well-filled bookcase 90º to the side of the speaker the subjective balance of that speaker will surely be different to having a glass wall at that point in the room relative to the speaker. Thus the speaker designer has to consider the room environment as part 'of' the speaker listening experience: the amplifier designer needn't care a jot about the speaker or the room; he can live in blissful ignorance and disinterest about anything downstream of his glorious amplifier creation, anything outside his laboratory. He needn't even listen to music. He needn't even connect a speaker at all to his amp - he could work from the lab technical measurement alone. You'll appreciate then that the amp and speaker designer are living in completely different worlds, and sadly, as we will see, the amplifier designer's incessant mantra that the amp's tone controls will somehow ruin his precious sound (and that they have no place in an audiophile amp) is as example of his complete detachment from the reality of real speakers in real rooms playing real music listened to by real people who just want the best possible - most realistic - sound at home. I state my position again - and this paraphrases what QUAD's Peter Walker said - it is logical to provide the listener of some means - acoustic, mechanical or electrical - of adjusting the perceived sonics of the recording/speakers/room/personal taste to give that home listener a fighting chance of recreating the concert hall experience. Since most home listeners living in the real world are unable/unwilling to apply mechanical (acoustic) treatment to their living space for cosmetic or cost reasons, then it is the duty of the amplifier and/or speaker designer to provide that means of adjustment for best possible sound. And the easiest way to empower the listener with the tools he needs is to build into the electronic chain (say, the amplifier) some "tone controls". Yes, some simple boost/cut frequency correction could be (and have been) built into the speaker's passive crossover, but the very simple topography of the passive crossover means that such tone adjustment controls would be very crude in their effectiveness, have a broad-brush application over wide audio bands and would most likely be of only a cut nature in the middle frequencies and of a boost in the upper frequencies, and at high cost. Tone control shaping circuitry in the amplifier should be extremely effective: as narrow or as wide a bandwidth range as needed, and with as much boost or cut in those bands as you would ever want. And all for just a few dollars. The amp is the natural choice for where to place any tone controls. Precisely what Peter Walker said half a century ago. Make sense so far? Let me know and then we can move on to look at what 'tone controls' do and why. Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ OK, before we get much deeper, please have a look at the first attached picture. There is so much commonality in photography and its light spectrum and sound and its audio spectrum. Look at the neutral greys, whites, blues and especially reds in that image. How do they look on your monitor? The reds look greatly overblown (over-saturated) to me. They ruin the overall balance of the scene. If we visualise that picture as a sound-scene, a musical performance where the colours are instruments, those over-saturated reds may be the equivalent of the over-blown bass end of the audio spectrum which is so typical of home listening, simply due to the room having inadequate absorption in the low frequencies. Getting an overall neutral picture image or sound image is why lighting technicians and acousticians earn their money: they design environments that add as little as possible to the scene being photographed or sound recorded. When we see a colour is prominent or deficient in an image, or a part of the audio spectrum likewise sounds prominent or weak, we have just observed that specific colours or sounds are louder or softer than they should be. We then describe the image or the recording as 'unnatural', 'unrealistic', 'too bright', 'harsh' and so on. These words are simply a shorthand non-technical way of saying that the energy in certain regions of the light or sound spectra is more than we would expect were we at the live venue. Or to put it in simple words 'the reds are too loud - they shout at you' or the 'bass end of the spectrum is too rich - it adds a warmth to every type of music that is played'. See how we can easily switch between our optical sensitivity to colour and our sonic sensitivity to sound? The language is almost identical because the issues are too: of an excess or leanness of energy in certain bands. And in my picture of the over-saturated reds, were we to put a volt meter on the camera image sensor's red channel output we would see that there was a higher voltage there than for the green and blue channels. And the sound equivalent is that, if we measure the frequency response of the typical speaker in the typical room and connect the microphone to the same volt meter, when the frequency range under measurement is at the low end of the audio scale, the microphone would generate a higher voltage in response to the more prominent sound waves in the typical room. If we can accept that our eyes and ears are sensitive to the 'loudness' of colours or sounds then we are really on the road. We observe the tools the professional and serious amateur photographer uses every day, without hesitation, as part of his job, to reduce the loudness (or sometimes to boost the loudness) of colours in his image. And we know that in the sound world, we also have loudness adjusting tools available to use. We really shouldn't reject those tools - they are our friends. The photographer's magic correction tool box is called Photoshop (or equivalent). The listener's toolbox is called 'tone controls'. They just do the same thing - selectively adjust loudness. Nothing more, nothing less. The audio tone controls do not change the pitch of the recording; they do introduce distortion; they do not alter the stereo width; they do not degrade the dynamic range; they don't have any of these unwanted side effects. They just change the loudness of certain user-selected frequency bands which, if those bands correlate with the sonic character of musical instruments, may make them more or less audible. Now compare with picture B - where I have reduced the loudness of the red end of the light spectrum and the image now looks correctly balanced. I have merely adjusted the images red colour (= bass tone) control. Nothing else has changed, but our perception is now that B is a much more natural and life like image. It's the same as using tone controls (or mechanical damping) to improve the sound of my listening room. Why wouldn't I want to do that if my goal is naturalness? Why on earth would I reject out of hand the very tone control tools devised 50 years ago that allow me to make those adjustments? Why would a photographer point-blank refuse to use Photoshop? More later.... (sorry, just as I returned to this, a WW2 Spitfire started a looping the loop flying display just a mile from home, a lady pilot ... Thanos would have enjoyed!) Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK http://www.harbeth.co.uk/usergroup/forum/the-science-of-audio/how-humans-hear-essential-reading-for-hifi-buyers/psychoacoustics-simplified/1478-tone-controls-the-ear-and-the-audiophile-curse-or-saviour 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 07:42:15 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 07:40 |

| [#1864] Tone Control #2 Tone controls # 2: the audio colour spectrum ... Directly continued from post #5 in this thread .... Before we can proceed much further I think we need to be able to interpret a 'frequency response plot' or graph or chart. Then we can make sense of the shape and characteristics of tone controls when we see their characteristics plotted onto a graph. Sound is invisible and very hard to visualise. We can hear its character and power but we can never see directly. So the first step is to emphasis that we can (and should) always try work with terminology that gives us an equivalence of effect but in a more intuitive way. We can use the light spectrum to give us an entirely adequate analogy of the sound spectrum. So, please take a look at the attached standard frequency response chart (literally a printed blank sheet torn-off a roll of pre-printed paper) which in the days of the pen chart recorder was the standard way of plotting sound loundness versus frequency. I've modified it. Along the horizontal axis we see the familiar 20Hz to 20kHz (actually the chart extends to 40kHz) sound bandwidth which is considered to contain all the frequencies detectable to the perfect (youthful) human ear. The Y axis, the vertical axis, is ruled in repeating blocks of fine lines - each one representing one decibel - with a major fatter line every 10dB. Each on of those five, 10dB vertical cycles is as good as any other in describing a 10dB change in nature, and this chart is capable of showing a frequency range from 20-20kHz and a loudness (aka dynamic) range of 50dB. Normally, just for neatness, we'd position the pen arm arbitrarily somewhere in the middle of the graph and not use the whole of the graph paper sine every 10dB block is interchangeable with every other cycle. Important note: unlike a business graphic chart, there is no 'zero' line. When we are working with dBs we are working with relative measurements so we can pick any vertical line as our reference, and then draw whatever we want to show as a variation above or below that reference line. So frequency response plots are nothing more or less than graphs showing the variation of loudness (actually, usually voltage or sound pressure level) relative to an arbitrary but fixed reference that we pick at the start of the measurement. In the good old days of the pen chart recorder, once we'd loaded the paper roll onto the motor unit, we'd twiddle the ink pen arm until the nib was aligned neatly somewhere vertically along the chart's dB scale, and then start the motor and make the trace. I used to prefer to line-up along the thicker 30dB line (just above the middle of the chart height) just for neatness. Now, we can't visualize sound but we are all familiar with the colours of the rainbow. So let's overlay the rainbow optical spectrum onto the graph, aligning it so that the redest red is on 20Hz and the most violet violet is adjacent to 20kHz. This is just my interpretation of sound v. light: there is no formal association between these! You are free to invent your own representation which would be equally valid. You could even reverse it so that 20Hz is violet and 20kHz is red. The reason I picked this particular spread with red at the low end of the spectrum is because we often associate adjectives like 'warm' and 'rich' with low frequency sounds and conversely, we use words like 'piercing' and 'sharp' for issues towards the top end of the sound spectrum. If you've seen a flashing blue light on an emergency vehicle you'll know how sharp it is and how it immediately grabs your attention - even in daylight. As for the other colours such as green, well that just falls as it falls in the spectrum. OK so far? No we have this relationship between sound and light across the audio band we can use the power of picture tone controls (which is what Photoshop is all about) to take manipulate images and to demonstrate the vertical scale of our chart. To be continued .... Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK http://www.harbeth.co.uk/usergroup/forum/the-science-of-audio/how-humans-hear-essential-reading-for-hifi-buyers/psychoacoustics-simplified/1478-tone-controls-the-ear-and-the-audiophile-curse-or-saviour 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 07:30:25 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 07:29 |

| [#1863] Tone Control #2 Tone Controls #3 - the perfect execution of the tone control concept I haven't had any feedback as to whether this subject is of interest or not so I hesitate to probe any deeper. However, it seems that the genius of the late Peter Walker of QUAD has done much of the work for me in developing the fantastic QUAD tilt control. I'm not saying that the QUAD vintage 80s preamp is the ultimate in fidelity. It may or may not be: I don't actually care. I've found the 34/44 tone control to be absolutely ideal for getting the best out of any speaker in any difficult listening room at home. As I have said many times, all amplifiers designed to make good music at home in untreated acoustics ideally need some sort of tone control to get the best possible sound out of the environment. Without tone controls, the user is really missing-out on optimising the best possible speaker/room interface. Although I have no personal experience of the later QUAD 99 (I've never actually seen one) the 99 downloadable user guide states on page 11: 'The bass control has one position of lift and one of cut. This can be used to rectify deficiencies in a recording or to compensate for poor room acoustics e.g. where speakers are placed too close to a corner etc..'. That real-world appreciation of how speakers actually behave in the typical living room endears me greatly to the brand. We'll look specifically at the QUAD bass control in another port; this time I want to concentrate on the QUAD-type tilt control*. Now, a few post back, Pluto, a sound engineer, kindly gave us a frequency response plot for the boost and cut versus frequency for a typical 'Baxandall' tone control. The Baxandall circuit we can say with reasonable confidence is used in every amplifier except QUAD. QUAD don't use a bass and treble control: they use a tilt control. That's a significantly different animal, and if Harbeth were ever to make an amplifier, it would feature a tilt control with characteristics similar to those of the QUAD tilt control. Fig 1 and 2 show the front of the Quad 34 from which we can see two tone adjuster controls: the bass lift/step control and a tilt control. There are no conventional bass and treble controls. It's another tribute to the QUAD team that the physical rotation of the paddles gives you a perfect indication of what measurable and sonic effect you will experience. These control are highly intuitive. If we look at the tilt paddle we see a really clever thing: depending upon how we turn the paddle we can have either less bass and more top or more bass and less top pivoting about a centre frequency. This single overall tilt control has a functionality which is totally different to a conventional bass and treble control. A conventional bass and treble arrangement with two independent control allows us to have any crazy combination of bass and treble simultaneously because there are two knobs. We could go mad and turn the bass and the treble fully up or both fully down. We can really destroy the neutrality of sound by the random and injudicious use of the conventional tone controls. But with the tilt control, all we are doing is applying a gently upwards or downwards bias to the overall sound shape. What Peter Walker appreciated was that, relative to (acoustics issues are always relative to something) a central frequency where the ear is known to be sensitive (around 1kHz) what was wanted was a little shading of the overall balance giving a slight preference (or mild emphasis) to these frequencies above 1kHz and simultaneously as slight de-emphasis to those below, or vice versa. The reason the effect was simultaneous is because in the real world what audiophiles find in a typical listening room is, for example, that there is 'too much bass', the 'bottom end is muddy', 'the room is boomy' or conversely, the room is 'too bright', the top end is 'too sharp', the upper frequencies are 'brittle'. We never seem to experience a combination of these unwelcome low and high frequency problems together do we. When did you hear someone complain of a room which was simultaneously 'too rich and too brittle' - most likely the opposite would be found: the room would be simultaneously 'too rich' and 'rather dull in the treble'. That's how real rooms behave with real speakers. So this tilting idea of applying a little gentle shaping is really appropriate. QUAD are reported saying, "The results obtained from any programme source depend on the aggregate effect of the listening room and the recording environment together with the (tone) corrections applied by the recording engineer, and the equipment of the reproducing chain and it is extremely unlikely that the arbitrary combination of these variables when listening at home will will yield the closest approach to the original sound... The TILT control can improve the subjective quality of musical reproduction, while adding no colouration, just a simply slight increase or decrease in overall warmth or brightness." So that's the rationale. I've measured the shelving up/down characteristics of the QUAD 34 - attached. Remember! If you follow the coloured traces depicting the dB boost/cut action versus frequency you'll see that you cannot have a random combination of bass and treble boost or cut. Bass and treble are linked so that if you pick maximum boost in the bass (blue curve) you will automatically have maximum cut in the treble (also blue). This is unlike a conventional two knob bass and treble control with complete isolation between the controls. Now we can overlay the characteristic curves of the tilt control onto my previous rainbow plot with it's familiar 50dB range [this revised graph is to follow]. I've carefully adjusted the measurements to overlay perfectly on the paper chart and now we can see the truth: the QUAD control has an extremely benign action of only about ± 3dB in either the bass or treble ranges. And also, as we'll see in the next post, the boosting or cutting flattens out - unlike Pluto's conventional bass/treble curve which continues up or down to infinity. Taken together, we can see that not only is the QUAD control really rather special in its aptness for room correction in just the one control, but that it has a very subtle correction range unlike the conventional controls. Yet the circuit is no more complex or costly to implement. In my long-term view that all amplifiers really would benefit the user with some sort of room-compensating tone controls fitted as standard. Whether the QUAD sound is for you (and I know nothing about post 80s QUADs) I'll leave for you to decide. But it could be that if you have a challenging room in which no speaker sounds right, a gentle use of the tone controls, sensitively applied, may well solve your sonic problems. I'd next like to look at how the typical room messes-up the low end of the loudspeaker. * The circuit used by QUAD to implement the tilt control is almost certainly public domain. A I recall, it was an implementation of the Ambler circuit which appeared in Wireless World in March 1970, some years before the QUAD 34. Note the comments on page 1 of the usefulness of tone controls in adjusting the recording and of how the operation of conventional bass & treble controls becomes more extreme the more they are turned up or down. The QUAD implementation took the Ambler concept for very benign adjustment and added, in effect, speaker/room correction with the secondary bass tilt /step control, on the left of the QUAD panel. Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK http://www.harbeth.co.uk/usergroup/forum/the-science-of-audio/how-humans-hear-essential-reading-for-hifi-buyers/psychoacoustics-simplified/1478-tone-controls-the-ear-and-the-audiophile-curse-or-saviour 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 07:28:00 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 07:27 |

| [#1862] Tone Control #2 Tone Controls #4 - low frequencies in the home listening room We've looked at the tilt control and how it is useful for increasing or decreasing sonic energy in the low or high frequencies, centred about a pivotal frequency. That can be most useful to compensate for a disliked trend in the recording, the room or the speakers. If the recording has a general tendency towards more warmth in the bass range than we'd like, a tone control can re-bias the energy (the perceived sound balance) away from the bass and more towards the top, and vice versa. That's fine if we have a general trend low-high trend, but what if the overall balance is deemed acceptable but we have a specific problem only in the lower frequencies - and the mid and top are considered OK. That's a very typical situation when listening at home. It's a fact that when most loudspeakers are introduced to most rooms — even to those rooms with (thin) surface treatment which is an effective absorber in the mid and especially high frequencies — there will be more bass than the speaker designer intended. So why doesn't the speaker designer take into account the reality of putting his nice speakers, designed and perfected in his laboratory or anechoic chamber, into a listening room? Good question. The honest answer has to be this: the variation in acoustic environment between a Tatami rice paper-walled living space in Kyoto and a 60s concrete apartment tower couldn't be greater. The traditional tatami build has walls that are acoustically transparent; the high-rise walls are completely reflective. Which one does the speaker designer consider his reference when creating a standard product to be sold and used globally? The answer is that the speaker designer has to have a general awareness of how the acoustics of a 'typical' living space impacts on the carefully considered sonic balance of his speakers, and that really is the best that he can do. What is typical? That really is a tough one. I suppose that, based on his observation of the demography of his customers he gradually develops an awareness of the 'average' customer's listening space, musical tastes, sonic expectations and so on. But this is not a science - speaker designers do not spend years travelling the world with test equipment measuring the acoustic characteristics of home listening rooms. Perhaps they should, but what then when they come to analyse all the accumulated data: there would be as many rooms which due to their construction tend to emphasise bass as there are are rooms which soak-up bass - the two extremes would tend to cancel out to yield an 'average' room. So, the easiest way for the speaker designer to proceed is to take his precious new designs into an anechoic chamber — a room without the sonic character of a room thanks to lots of absorption — and, put out of his mind the inevitable contribution of the highly indeterminate listener's room. In other words, the speaker designer is obliged to resort to a standard listening environment (the anechoic chamber) and to accept the fact that in every single real world room his speakers will behave differently, perhaps markedly so. But what else can he do other than designing one-off bespoke speakers individually tailored to a specific millionaires listening space. There are two things which mercifully come to the speaker designer's assistance, without which "high fidelity" listing in the normal home would be utterly impossible. The first one is that the deleterious effect of the home listening room is primarily in the bass and lower midrange - say, the red and yellow frequency regions in my coloured charts above. The second one (thankfully) is that most people actually prefer the low frequencies to be a little 'warmed-up' when they listen at home compared with real life. They may never have experienced live musical instruments to be aware of this, but we are so conditioned by the sound of speakers at home that we have lost, or never actually had, the connection with the live sound. Taken together then, this generally experienced bass lift in the real-world domestic listening room (due to inadequate absorption at low frequencies) plus the user's preference for a little extra bass 'weight and warmth' contrive to the speaker designer's advantage and within reason, he is safe to continue to design in his 'flat' anechoic chamber aware that at home, his speakers will fulfil the listeners preconditioned expectations in the bass region. OK so far with this? Now we can take another step forward. Those speaker designers that do get out and about occasionally with test equipment in 'typical' domestic listening rooms have observed some generalised sonic characteristics in those rooms. That is not to say that every room behaves in the same way. Nor is it to say that there is somewhere the 'standard' room which everyone could use as a domestic reference with the owner renting it by the hour for acoustic measurements!. All we can say is that there is a certain pattern that has developed by observation that seems to suggest that, as a generalised observation, if we measure a loudspeaker that has a flat frequency response in the anechoic chamber, that response will take-on a certain characteristic low frequency energy boost (due to inadequate absorption in the listening room) when placed in a normal domestic room. And that dB characteristic low-end boost can be drawn on chart paper v. frequency. Important! As I said above, the gentle boost associated with extra energy in the low frequencies of the listening room may not only be of no concern to the listener it may actually be mandatory for a satisfactory 'lifelike' experience in the listener's mind. So what do the archives indicate is a 'typical' low frequency boost typical of home listening? There is little published literature on 'room gain at low frequencies'. This is an issue which has not been given much attention and largely ignored. Other experimenters and theoreticians will have their own data, but they will not greatly change the overall picture that normal domestic listening rooms crank-up the loudness of, and introduce peaks and troughs into the otherwise flat response of loudspeakers. Here is a working observation: We know that most room issues that draw attention to themselves are in the lower frequencies We do not know exactly what those frequencies are - they may vary from room to room or even position in the same room We do know that there is often a generalised warming-up of the lower frequencies i.e. there is 'room gain' at low frequencies We do not know at what frequency that room gain starts to take effect or fades out - for example, becomes measurable at 500Hz and increases in effect right down to 20Hz We do not know if the room gain is a certain number of minimum, typical or maximum decibels boost Any fancy graphs we produce can be no more than crude generalisations and approximations at best That's quite a few unknowns. Practical experience shows that the acoustic theory significantly over-states the actual bass lift because real rooms have losses, turning sound energy into heat. What seems to be a believable lift found in a 'typical' home environment is of about +10dB at 20Hz relative to 1kHz, as shown on the attached chart, from Tolvan Data. This chart is probably an understatement of the behaviour of many rooms - but it looks about right to me as a minima. Do bear in mind that the nice, smooth, regular boost curve is a highly idealised situation. In reality, the room's boost characteristic will be highly irregular; the best we can do is to draw a mental line through the lumps and bumps to get a trend line, as shown. Next we can see how easy it would be for us to use our tone controls to cancel that room lift, assuming that we would wish to do so. P.S. Please, no calls or emails saying that that having read this post you are now in a mental spin about your system. If you have enjoyed whatever sound you have enjoyed for years, continue to do so. There is already far too much needless unhealthy anxiety in high-end audio without adding to it. Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK http://www.harbeth.co.uk/usergroup/forum/the-science-of-audio/how-humans-hear-essential-reading-for-hifi-buyers/psychoacoustics-simplified/1478-tone-controls-the-ear-and-the-audiophile-curse-or-saviour/page2 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 07:23:21 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 07:22 |

[#1861] Tone Control #2  Klark Technic DN27 graphic equaliser What about DSP? To answer the last few posts .... First, I don't necessarily think that the QUAD 34/44 is the ultimate solution to a modest rebalancing of the room sound. It certainly is one solution, and as these units are so inexpensive it may be worth the flutter, but you would have to buy-into the whole circuit philosophy and, importantly, the gain structure. That means that the preamp could be overloaded by a strong CD signal (above volume control mark 14 or so) and the output is designed to drive the rather sensitive QUAD power amps, such as the 405/606. An alternative solution would be for someone to built a little box that either sits in the tape out/in loop of the preamp, between the pre and power amp, or perhaps a digital implementation between digital source and DAC. If anyone had the skills to make such a unit, they should contact me directly as we would be interested in such a design. We dedicated audio enthusiasts just want the best sound we possibly can achieve at home (with whatever speakers from whatever brand we have) without calling in the builders for serious structural work. 'Tone controls' however electrically implemented are a possible aid to that. But at this stage of the game when DSP solutions are so elegant and cost effective, I'm wondering if a more holistic approach has merit. The implementation of QUAD-like tone control shaping circuits in a DSP chip is utterly trivial, perhaps only using 1% of the computing power. Can't we do something with the remaining 99% processing capability that would solve other speaker/room issues, basically for free?  Klein & Hummel UE400 stereo equaliser To that effect, it's been on my mind for the last few years to have a serious look at DSP and I made a brief pilot test a couple of summers ago. The overarching concern is not the technology, but how to bring it to market. There are several issues: Explanation, training and demystification (removing the fear of the unknown) If there is so much hostility to simple analogue tone/tilt controls amongst amp makers/media how about any DSP concept? Recognition that every listening room has different acoustic issues so a 'one size fits all' is not technically viable (although a marketing need) Deciding who 'trains' the DSP to the listener's room: does the user have the skills and patience? Could the sound actually be worse with an incorrectly applied DSP solution (yes!!! definitely worse!!) The potential for never-ending confusion and anxiety by the listener Role of the distributor/dealer in supplying DSP solution and after care Recognition that DSP technology is not core to Harbeth's business - would it become a serious distraction? Can 'DSP Ambassadors' be established per country to work alongside customers and dealers to set-up and tune the user's home systems? Supply route for DSP hardware - through existing Harbeth sales channels or not? What if user changes speakers/room? Reprogramming? Potential for mischievous media/competitor to claim that Harbeth speakers 'only sound good with DSP help'. Is there a (small) profit to be made? That's a lot of questions. All needed to eb resolved. I'm off on holiday shortly and I'll take my notes with me (on my wonderful new Fujitsu M532 tablet - thinnest on the market) and re-read where we got to. Implementing QUAD-like tone controls, conventional tone controls or just about any sort of tone shaping you can dream of plus local speaker-only optimisation or speaker + room optimisation is all very much doable with current technology. Please, unlike the amplifier project which was stamped-out at conception, can we set aside the internal business related issues of whether we should pursue this project at all - they are really for me to balance - and focus on the above issues. I'm sure you'll agree that it is a privilege to discuss this openly; let's not strangle this project. In the meantime, I found Studio Sound (pro) magazine from 1976 in the archive. Attached is a review of the ubiquitous Klark Technic DN27 graphic equaliser and the Klein & Hummel UE400 stereo equaliser. I think it's safe to say that, pre-digital recording, the audio signal in the vast majority of recordings from the 70s and 80s probably passed through boxes like these. Scan of 'classic' analogue EQ solutions attached. The DN27 gives 1/3 octave band boost and cut at spot frequencies exactly as Pluto described in post #6; the UE400 is more like the QUAD tilt control I've described with broad sweeping effects. It is entirely possible that the recording engineer would pass the signal serially through both - the DN27 to adjust the tonality of specific instruments or vocals, and the UE400 to give an overall tilt to the sound balance. Don't ever think that commercial recordings are recorded 'flat' - lots of eq is normally applied. Equipment like these analogue boxes would be a theoretically valuable tool to adjusting the sound of your room. Whether these boxes are sonically 'pure' enough for you, I cannot decide. Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK http://www.harbeth.co.uk/usergroup/forum/the-science-of-audio/how-humans-hear-essential-reading-for-hifi-buyers/psychoacoustics-simplified/1478-tone-controls-the-ear-and-the-audiophile-curse-or-saviour/page3 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 07:18:58 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 07:16 |

[#1860] Tone Control #2   Missing Sonic Controls https://www.tubecad.com/2013/06/blog0266.htm Missing Sonic Controls (Sonic Control) http://www.tubecad.com/articles_2002/Missing_Sonic_Controls/Sonic_Control.pdf Sound Reproduction: The Acoustics and Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=tJ0uDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT179&lpg=PT179&dq=quad+tone+controls&source=bl&ots=QI8uwuY9ec&sig=ntL2a_m8UAsw4GGlv-wIXWjnEXo&hl=zh-TW&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj9nZfeo9rXAhWFKpQKHSGbCRgQ6AEIfTAN#v=onepage&q=quad%20tone%20controls&f=false 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 07:00:19 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 06:58 |

[#1859] Tone Control #2   圓夢記 -舊愛成新歡(2) http://blog.xuite.net/newbjman/hkblog/147303653-%E5%9C%93%E5%A4%A2%E8%A8%98+-%E8%88%8A%E6%84%9B%E6%88%90%E6%96%B0%E6%AD%A1%EF%BC%882%EF%BC%89 圓夢記- Cello潛力釋發的三招 http://blog.xuite.net/newbjman/hkblog/expert-view/147303617 圓夢記- Cello潛力釋發的三招(2) 雙重過濾,重組配線 http://blog.xuite.net/newbjman/hkblog/147303610-%E5%9C%93%E5%A4%A2%E8%A8%98-+Cello%E6%BD%9B%E5%8A%9B%E9%87%8B%E7%99%BC%E7%9A%84%E4%B8%89%E6%8B%9B(2)+%E9%9B%99%E9%87%8D%E9%81%8E%E6%BF%BE%EF%BC%8C%E9%87%8D%E7%B5%84%E9%85%8D%E7%B7%9A 最後修改時間: 2017-11-26 01:40:15 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-26 01:39 |

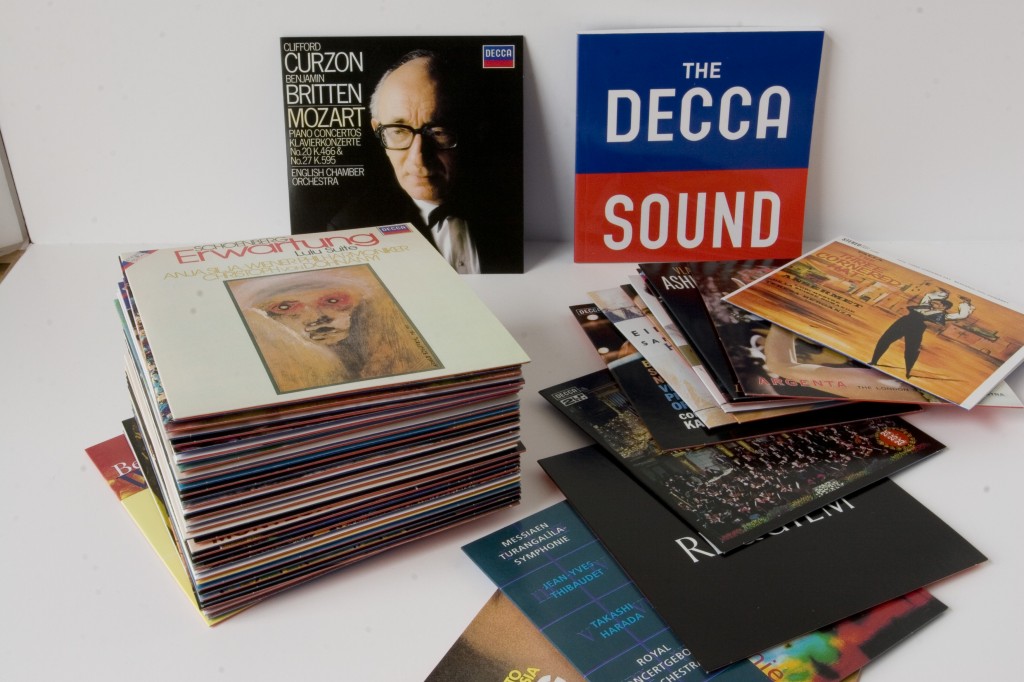

[#1858] Tone Control #2  " The Decca Sound Differentiating the Decca sound from that of EMI by ear alone is not necessarily an easy thing to do, but Mike believes that the tracking method used by Decca caused them to mix in a particular way which can be heard on the record. “The key to understanding the difference between Decca and EMI,” Mike explains, “is that Decca always wanted to mix to two tracks, although they had four-track backups as early the late ’50s, in case they needed to track in a singer who wasn’t on their best day, or rebalance. But the whole concept of Decca was mixing to two-track. EMI went to four-track in the mid ’60s so their records weren’t produced in stereo at the session like Decca’s.” Mike is also keen to point out that something as fundamental as the choice of microphones had a defining affect on the general sound of Decca’s output. The Decca sound was really the sound of the microphones,” he insists. “The M50 was omnidirectional, designed for the German radio, with a boost at the top and that was a famous Decca trait from the age of 78s, although it was tamed a bit when the discs were cut. Later they mainly used KM56s and KM53s because they were small enough to put on stands in the back but eventually they started using bigger Neumann U67s, U88s and a whole variety of spot microphones. There would often be spots behind the horn section, percussion, on the woodwind, and that also became a Decca trademark. “They didn’t necessarily do that at EMI. But it is hard to generalise beyond the microphones and two-track, because they listened to each other’s work. There were sessions at EMI in which their record would be played against the Decca record. They were listening to each other a lot so there was sort of a convergence.”  BSO Torke Sessions, October 1990 Tailor Made From studying the documents relating to the equipment, recording methods, setups and venues that Decca used, it is possible to build up a reasonably clear picture of how their signature sound was created. Nevertheless, there is yet more to it than that data alone seems to suggest, as Mike reveals. “Everything was tweaked by the backroom guys. They might replace a microphone’s tube with a MOS-FET, or change some of the resistors to flatten it out, but the key point is that none of the equipment was stock. There was always something done to make it better – make it Decca; put the Decca imprint on it. That was, I think, the genius of Decca: the people doing the mixing were also telling the maintenance guys what they needed. That was Arthur Haddy’s work. Haddy was an engineer to his boots and wanted everything to be just right and that’s what they got. “Roy Wallace built many of the Decca portable mixers, such as the Storm 64, which had the ability to mix 24 microphones into two tracks and was used all over the world. He developed the cleanest, simplest and most flexible mixers and it was all built in-house. You didn’t go to Neve in those days, you built your own. “But the gear was nothing unless you had operators who knew how to use it. It’s inaccurate to say it was flat at the board because they made adjustments depending on the piece of music and where they could put the microphone. If you look at the Electrical Records of Session you see all kinds of fixes on the way to tape. Unless you see these documents in bulk you don’t realise how much tweaking was done to get the sound onto the tape, in the way they wanted it. “In a pan situation a microphone would be a little bit left or right, there was always EQ used on the board, either a little less bass, a little more treble; plus this, minus that, on the way to tape. So for instance, the tympani might have its own mic but it would be minus five at the bass. Somebody else would have plus three at the top for a little bit more bite.” FULL ARTICLE: http://www.polymathperspective.com/?p=2484 最後修改時間: 2017-11-13 02:04:08 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-13 02:01 |

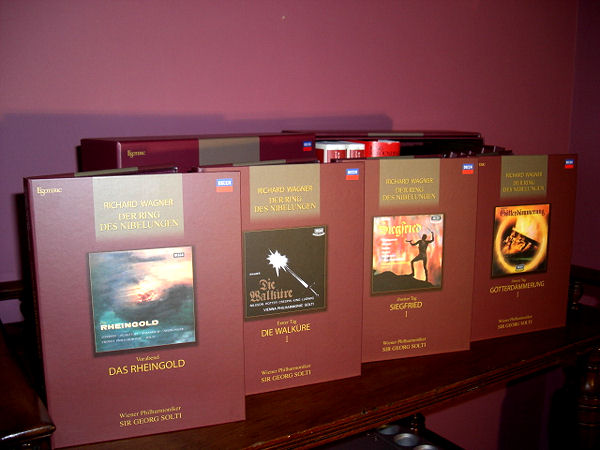

[#1857] Tone Control #2 :format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7674089-1465739202-7708.jpeg.jpg)  A tribute to a fabulous recording - Benjamin Britten's 'Peter Grimes' 24-03-2011, 09:56 PM Introduction: I've mentioned a few times this wonderful and pioneering stereophonic recording from 1958, recorded in the second year of the stereophonic era. Even if you know nothing about the format of opera, or don't think you like opera (I'm not a great fan of opera myself) this is the one to have. The performance is conducted by the composer and the recording atmosphere is simply fabulous. These early Decca recordings hooked me on audio in my teens - the first I bought was the 1969 Billy Bud. I wanted to create speakers that would put me right there in the recording venue and make those voices sound as if they really were in front of me, in my listening room. So I'm looking forward to taking you back half a century to north London to the performance conducted by the composer himself. It is absolutely certain that if the same cast, orchestra and composer could be assembled today in the same hall, probably using the same microphones, modern digital recording would offer a technically superior sound. If you know the recording as well as I do, you'll be all too aware of its occasional technical blemishes. Nevertheless, it is what it is and the atmosphere forgives the limitation of the 50s technology. Perhaps we can look at those little foibles later. I mentioned recently that Decca records - specifically producer John Culshaw - consciously set about using the possibilities of the then novel idea of the stereophonic L-R width to create on playback at home a really absorbing experience. That was in stark contrast to stereo demonstration disks of the era with their blatant L-R ping-pong effects. We'll cover them another time. We can also hear that by 1961 and Noah's Flood just three years later - there had been a significant improvement in recording quality. About twenty years ago when Decca had their analogue tape archive in North London, I visited them and specifically asked to see the original 10.5" Peter Grimes NAB tape reels. We wandered along what seemed like mile after mile of archived tapes all neatly arranged on shelves and eventually found them. I just had to hold one. At the time the only way of editing was to take a razor blade to the master tape (or a second or later generation of it) and once the cut was made, it was permanent. If I recall correctly, there were notes on the box mentioning that there were indeed numerous edits and that some of them, held together with by-then thirty year old sticky tape were very fragile indeed. So the master tape itself, believed to be first generation had been physically spliced with great skill within weeks of the recording. What I had in my hand was a time capsule of a recording venue from the very earliest days of stereo. Many of those involved are no longer alive, so this is my long overdue tribute to them*. (Tape editing and digitisation is another story for another time). The original tape to digital transfer was made in 1985, and it wasn't my friend who did that one - but it surely would have been on a Studer A80. I don't recall what digital format it was transferred to: Decca had pioneered the use of digital audio to videotape but having been taken over, probably fell into line with Philips corporation-wide policies and procedures. It really doesn't matter - the fact is the old tapes were transferred to digital before they faded away and we lost this beautiful performance. This week I found that Amazon were offering a '96kHz, 24 bit' version of Grimes which has arrived. On a quick listen, I can't hear any difference between than and my original 44kHz, 16 bit version, nor would I expect to: the limiting factor by far is the analogue tapes from half a century ago. The twin CD package doesn't include the libretto, so if you are interested in buying, I'd strongly recommend the original full price if still available just for the libretto. What I'd rather have had for the money is the skilful use of modern digital noise reduction to remove one or two noise artefacts which, when you know the recording well, are audible. They are most likely to be the result of tape storage issues: you have to nurse old analogue tapes which by their very nature, start to self erase from the second they are recorded. So that sets the scene. Now to have a look at the layout of the recording stage on the next post ... * I've just remembered that I used Peter Grimes as a demo piece at the old Penta/Ramada hi-fi show in London many years ago - probably mid 90s. One member of the audience came over to me and said that he'd actually been present at the recording thirty five years previously and the whole experience was so emotive that he just hadn't been able to bring himself to re-live it on record. We were both lost for words. He said some very kind things about the sound (I think it was either C7ES2s or HL5s) and on he went. I should have asked for his name. Alan A. Shaw Designer, owner Harbeth Audio UK http://www.harbeth.co.uk/usergroup/forum/subjective-soundings-your-views-on-audio/music-recordings-and-broadcast-sound/981-a-tribute-to-a-fabulous-recording-benjamin-britten-s-peter-grimes Kingsway Hall London The recording set-up in an ordinary public hall ... London 1958 London has several well known hall, the most famous being the Royal Albert Hall. But rival record companies Decca and EMI identified far less grand halls which, despite appearances, had excellent acoustics. The late Decca producer John Culshaw wrote in his autobiography about the Kingsway Hall .... (to follow) and the history of the Kingsway Hall can be found here. As you can see from the photographs here there is absolutely no clue from the outside that the acoustics inside were considered to be one of the very finest in the world. The hall was actually owned by a Christian organisation, and rented out as needed. Another famous hall was the utilitarian Barking Assembly hall - more on that another time. "Despite the drawbacks, Kingsway became the most sought-after recording venue for orchestral music in England because of its central location and excellent acoustics, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s when companies were converting from monaural to stereophonic recordings. The London Symphony Orchestra alone made 421 recordings there between 1926-1983; the London Philharmonic Orchestra made 280 recordings there, including its very first sessions (with Malcolm Sargent conducting choral favourites)." So, the appearance of the hall and its acoustics can be complete opposites. Decca made their first stereo test recordings in 1955 at Kingsway, but there were other London halls available to hire: Walthamstow Town Hall (also here)was where Grimes was recorded. Another good hall is the Barking Assembly Hall. There is no automatic corrolation between the appearance of the hall and its acoustics: sometimes, by chance, the acoustics 'just work'. Although e take it for granted now that stereo offers a life-like experience, in the 50s even amongst record company executives there was almost total apathy - even hostility - to this new fangled invention. The money men at Decca, according to Culshaw, with exceedingly hostile to the stereo concept. The public wouldn't appreciate it, didn't need it and wouldn't pay for it. It would be more complex to record and stamp LPs. A few subversive engineer/producers could see the potential. What was needed was showcase performances, planned down the the smallest detail for the best possible all-embracing stereo effect. That literally meant dividing the stage up into a clearly marked grid, going through the score bar by bar and asking the singers to move, left right, front back. The intention was that this would be captured to tape. And it was. Attached first picture of the arrangement at the Walthamstow Town Hall. You can see the composer/conductor Benjamin Britten on the podium, bottom left; the orchestra arranged in front of the stage with the usual left to right arrangement of instruments; the stage, raised about 1.5m above the orchestra with clear line of sight with the conductor; singers arranged across the stage left to right; the chorus far right and to the back. Note how the orchestra is facing the conductor, and for most musicians the singing on the stage is either fully or partially behind them. It's the conductor's skill that keep the entire stage and orchestra performing as one. We'll look at the microphones later. Another picture of the stage layout from above, clearly showing the grid matrix. If you look carefully between the radials 7 and 8 you can see producer Erik Smith (glasses, sleeveless jumper, black tie in grid sector 7D) and engineer Kenneth Wilkinson (glasses, toe touching 8B) and performers deciding upon exactly where to position themselves for the intended stereo perspective. This 1958 recording was planned in minute detail. Of Kenneth Wilkinson who died in 2004 it was said: "Everyone loved and respected Wilkie, but during a session he could be exacting when it came to small details. He would prowl the recording stage with a cigarette – half-ash – between his lips, making minute adjustments in the mike set-up and in the orchestral seating. Seating arrangement was really one of the keys to Wilkie's approach and he would spend a great deal of time making sure that everyone was located just where he wanted them to be, in order for the mikes to reflect the proper balances. Of course, most musicians had a natural tendency to bend toward the conductor as they played. If such movement became excessive, Wilkie would shoot out onto the stage and chew the erring musician out before reseating him properly. He wanted the musicians to stay exactly where he had put them. He was the steadiest of engineers, the most painstaking and the most imaginative. In all of his sessions, he never did the same thing twice, making small adjustments in mike placement and balances to accord with his sense of the sonic requirements of the piece being played." "The most remarkable sonic aspect of a Wilkinson orchestral recording is its rich balance, which gives full measure to the bottom octaves, and a palpable sense of the superior acoustics of the venues he favored, among them London's Walthamstow Assembly Hall and The Kingsway Hall of revered memory" 最後修改時間: 2017-11-13 01:51:47 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-13 01:46 |

| [#1856] Tone Control #2 Hi Fi 基礎談 十二:音響與音樂 七月 14 11:452017 by Hi-Fi 音響  一位錄音監製,經常可以隨意改變重播效果的音色,引起一些朋友認為我是個反 Hi Fi,反電聲的發燒友。其實錄音跟真實演奏兩件事在今時今日已可說是並肩而立、分庭抗禮。萬不可因為錄音是一種科技而忽視了它的藝術成就。相反地,錄音技術已經發展為獨當一面的崇高音樂藝術。 錄音技術目前已可說是臻達了無所不能之境界,但並不代表任何摩登錄音只要採用已知的最「完美」器材便成為「完美」錄音。理論上或者有人敢說,實際上成功的錄音除了要靠優良的技術及儀器之外,天時、地利、人和是左右錄音成績的三大要素。同樣一枝咪高峯,同一現場同一位置上,今日可以有美的效果,明天卻令人掩耳疾走。溫度、濕度的變化固然有影響,還有是可能永遠不獲解答的神祕之謎。 權威性見仁見智 若問錄音與真實演奏兩者那一種更為代表藝術上的權威性,答案就不容易決定。真實演奏較為像一幀繪畫,富於製造的即興性。錄音則相當於攝影,它的再造性經過精雕細琢。真實演奏仍然帶來動態上無比的滿足,又在視覺輔助方面,給現場的欣賞者增加玄妙的刺激。錄音卻像攝影一樣,可以運用種種黑房技術去製造各式各樣現場所不可能有的效果氣氛。  講到黑房技術,流行音樂錄音少不了。甚至,流行音樂的範疇,因為錄音特技效果的輔助而大大地拓張,流行音樂錄音為全世界億萬家庭提供了現場演奏不能比擬的伸縮性及變幻性。殘響的精巧運用,已達到鬼斧神工的境界;人聲重叠的特技,歷年來也創造了不少金唱片。改變磁帶的速度,善用數碼科技,又可以製造千變萬化的非自然音響。電子音響、迴響、磁帶速度、聲叠聲的綜合創作,已經儼然成為一門只在錄音創作品上出現的演奏藝術。今時今日,有名氣的流行歌手,無論在台上表演或錄音時都一定自備度身定造的咪高峯,以彌補其腔音的短處。在錄音時,除了特種咪高峯之外,更可巧妙地運用頻率均衡器「調諧」歌者的聲線,使歌手的歌喉更富於性格、更具磁力。總之,運用錄音技術,電聲學家就可以隨意創造一副人造的歌喉,任何虛有其表的小毛頭,只要有某種吸引潮流的氣質,給唱片星探們一連串的安排及再造,便可搖身一變,成為一位唱片界的新星。不少流行歌手,基於本身質素所限,都不便輕易舉行演唱會,就是這個原因。 利用混音技術和殘響技術灌出來的唱片,不僅捧紅了大把歌星,而且捧紅了大把樂隊。顯赫一時的曼道凡尼大樂隊 (Mantovani),在演奏廳裏給人的印象完全跟聽唱片是兩回事。Phase 4 唱片最暢銷的身歷聲兩邊走流行音樂,娛樂性當時也具豐富的價值。  為了 Hi Fi 買指環 在古典音樂方面,錄音特技無疑是吸引全世界愛樂者深入欣賞的第一招。始作俑者就是迪佳公司的傳奇人物 John Culshaw。在身歷聲唱片問世的第一年 1958,Culshaw 和佐治蘇堤 (George Solti) 在維也納替廸佳公司賭下了唱片史上空前最大的一注;灌錄了華格納指環集的「萊茵河之金」。當年,買這套唱片的 Hi Fi 迷目的多數是為了欣賞歌劇的身歷聲效果及行雷閃電特技音響。 在錄音時,音量不足的歌劇獨唱者可以運用電子技術灌出成績優異的作品。不少年老或技巧差的鋼琴家在演奏技術困難的樂段時,左手部份隨時請替身瓜代。小提琴或大提琴獨奏部分某一段錄出一個不堪入耳的「酸」音時,剪接者有辦法為他矯正這個音符。逝世多年的偉大歌唱家所灌錄的歌曲,可以用「插入」技術配上嶄新的樂隊伴奏部分,以新演奏、舊歌聲的姿態再上市。凡此種種,衞道之士可以說是踏在脫離藝術的危險邊緣,但新潮之士也可以說它是藉以提高藝術水平的一種技倆。 愛廸生發明留聲機的原意,並不期望它他日會成為播放音樂的家庭娛樂玩意;他認為留聲機對人類的最大貢獻,將是對商業及教育方面的功用。他是無論如何也不會預見到 Hi Fi 器材能有朝一日深入至每一個摩登家庭。今日 Hi Fi 錄音技術,是人類文明進化的重大里程。發燒友不論成為 Hi Fi 的奴隸也好、善於享受人生也好,都應該感謝先進錄音技術為人類帶來更美好的日子。 「好」的錄音不一定「真實」 因此,好的錄音,並不一定是忠於真實的錄音。只要灌出來的音響富於美感,就算聽起來跟真實現場演奏相距甚遠,也值得拍爛手掌。Hi Fi 名家麥李雲信 (Mark Levinson) 在香港發表談話,曾猛彈 EMI 唱片錄音差,他認為 EMI 採用大堆頭咪高峯及多頻段混音器,使音樂中真正的平衡度受到破壞。他贊成每聲道只用一枝咪,極其量最多加一枝咪拾取殘響混入左右聲道而已。本港不少深入欣賞音樂的發燒友,對麥仔的「偉論」大表反感。固然,EMI 目錄上不少因為混音技術不妥而出現音色不平衡毛病的錄音,但音色豐滿美麗、令人愛不釋手的佳作亦復數之不盡。另一方面,幾間發燒級公司採用每聲道一枝咪的錄音雖然清晰透明,但有幾張最初十次八次聽得非常刺激的唱片,就愈聽愈覺其單薄。 靚聲的錄音就是好錄音 所謂條條大路通羅馬,靚聲的錄音就是好錄音,並不能以它是多咪錄音抑或少咪錄音而取捨。少咪錄音目前是一種潮流,看來它也有非常可取的長處,值得電聲界繼續去探索。但少咪式錄音的流行並不意味着多咪式錄音會被淘汰,因為多咪式錄音的伸縮性仍然強過少咪式。 最新出品的一些多咪錄音唱片,無論在音色的平衡度和動態範圍各方面,均有十分顯著的進步。古典音樂錄音風氣,近來已經脫離了初期賣弄音響效果的習慣,這是個可喜的現象。數碼唱片製作態度已反璞歸真,崇尚美麗的音色而摒棄膚淺的誇張。 全世界發燒友的欣賞口味是在提高之中。朋友,你近日愛聽甚麼? (原文刊於 1987 年 4 月號《Hi Fi Review》,作者 雷明 先生) http://hifireview.com.hk/20170714/hifibasic-12/ 最後修改時間: 2017-11-13 01:42:43 |

george1977v5 119.xxx.xxx.251 |

2017-11-13 01:35 |